Can the Bible Be Trusted? Part 3: The New Testament: Transmission and Textual Criticism

Greg Heil

|

10:20 AM

Part 2: The Old Testament: Transmission and Canon

Transmission

The books that make up the Old and New Testament canon were transmitted down to today’s Christians in quite different fashions. The Old Testament was mainly transmitted via professional scribes who copied it. Many of the people of the time were not capable of reading and writing, so there were people specifically trained to copy the scriptures. These people were called scribes. This was their occupation, and as such they did a high quality, professional job. There were very stringent guidelines in place dictating how exactly the scribes were to go about copying the scriptures. For instance, they had to count all of the letters on a completed page, to verify that they had done an acceptable job. If they had more than three errors per page, they were required to start over. This ensured a very, very accurate transmission of the Old Testament down to current times.

On the other hand, the New Testament has had a much more convoluted transmission to modern times. No one is currently in possession of a copy of any of the New Testament autographs. However, many copies are still in existence. Unlike the Old Testament, the New Testament books were copied by many, many people creating over 5,400 currently in existence, which is many more than the number of Old Testament documents.

However, the fact that many different people were allowed to copy the documents created many more errors as they were copied and copied again. But, the fact that we have so many copies in existence negates this problem, as the scholars are able to compare all of the documents and get a very accurate idea of what the original autographs contained.

Textual Criticism

Now, there has to be a method of deciding which readings of the various texts are contradictions, and which were in the original autographs. This method is called “textual criticism.” Textual criticism, as defined by the American Heritage Dictionary is “The study of manuscripts or printings to determine the original or most authoritative form of a text, especially of a piece of literature.”

To do a textual criticism one must first look in a Greek New Testament for a passage that is debatable. Second, look at the footnote for the passage in question, and note the letter grade (A, B, C, D) that the editors provided on the reliability of the reading. Then, examine the different manuscripts listed for evidence for the provided reading and against the provided reading. Basically, one must compare the three different types of evidences: the actual manuscripts, the early church fathers, and the other early versions/translations.

The most authoritative by far are the actual copied Greek manuscripts that are still in existence. Those must be evaluated on which family of documents they came from (Alexandrian being the best, Western being second best, and Byzantine being the worst) and the age of the document (the older the better). After that, move on to the early church fathers and the other early versions/translations. That is a brief summary of textual criticism.

Textual Criticism Case Study

I did a short textual criticism of 1 Peter 5:14. The word “amen” was in question, and the provided reading omitted the word. I checked, and the reliability of the given rating was only a “C” on the A-D scale (“A” being the best). Either way it is read, the editors really are not completely certain. I checked the end of 2nd Peter, and it included the word “amen,” but in brackets, to show that it also was in question.

Both the omit side and the add side had many documents from the Alexandrian family, and a couple from the Byzantine family. The dates on those documents ranged from the 4th century at the earliest all the way up until the 11th or 12th centuries at the latest. The division of dates was more or less equal for both sides of the argument. I arrived at the conclusion that it was difficult to tell which was the original reading in the autograph, but that if I had to choose one, I would probably choose to omit the “amen” (because that’s what the editors did).

Textual criticism is crucial, because it can help us decide if the translators did an accurate job with the text. Now, there are many, many different translations, and some people have been known to present the view that because there are so many, it is impossible to know what the Bible truly says. That view is false!

Part 4: English Translations

|

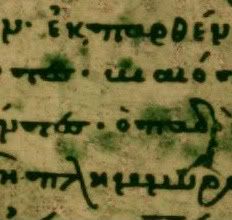

| New Testament Manuscript Photo Credit: CSNTM.org Manuscript Location: University of Michigan, Ann Arbor |

The books that make up the Old and New Testament canon were transmitted down to today’s Christians in quite different fashions. The Old Testament was mainly transmitted via professional scribes who copied it. Many of the people of the time were not capable of reading and writing, so there were people specifically trained to copy the scriptures. These people were called scribes. This was their occupation, and as such they did a high quality, professional job. There were very stringent guidelines in place dictating how exactly the scribes were to go about copying the scriptures. For instance, they had to count all of the letters on a completed page, to verify that they had done an acceptable job. If they had more than three errors per page, they were required to start over. This ensured a very, very accurate transmission of the Old Testament down to current times.

On the other hand, the New Testament has had a much more convoluted transmission to modern times. No one is currently in possession of a copy of any of the New Testament autographs. However, many copies are still in existence. Unlike the Old Testament, the New Testament books were copied by many, many people creating over 5,400 currently in existence, which is many more than the number of Old Testament documents.

However, the fact that many different people were allowed to copy the documents created many more errors as they were copied and copied again. But, the fact that we have so many copies in existence negates this problem, as the scholars are able to compare all of the documents and get a very accurate idea of what the original autographs contained.

Textual Criticism

Now, there has to be a method of deciding which readings of the various texts are contradictions, and which were in the original autographs. This method is called “textual criticism.” Textual criticism, as defined by the American Heritage Dictionary is “The study of manuscripts or printings to determine the original or most authoritative form of a text, especially of a piece of literature.”

To do a textual criticism one must first look in a Greek New Testament for a passage that is debatable. Second, look at the footnote for the passage in question, and note the letter grade (A, B, C, D) that the editors provided on the reliability of the reading. Then, examine the different manuscripts listed for evidence for the provided reading and against the provided reading. Basically, one must compare the three different types of evidences: the actual manuscripts, the early church fathers, and the other early versions/translations.

The most authoritative by far are the actual copied Greek manuscripts that are still in existence. Those must be evaluated on which family of documents they came from (Alexandrian being the best, Western being second best, and Byzantine being the worst) and the age of the document (the older the better). After that, move on to the early church fathers and the other early versions/translations. That is a brief summary of textual criticism.

Textual Criticism Case Study

I did a short textual criticism of 1 Peter 5:14. The word “amen” was in question, and the provided reading omitted the word. I checked, and the reliability of the given rating was only a “C” on the A-D scale (“A” being the best). Either way it is read, the editors really are not completely certain. I checked the end of 2nd Peter, and it included the word “amen,” but in brackets, to show that it also was in question.

Both the omit side and the add side had many documents from the Alexandrian family, and a couple from the Byzantine family. The dates on those documents ranged from the 4th century at the earliest all the way up until the 11th or 12th centuries at the latest. The division of dates was more or less equal for both sides of the argument. I arrived at the conclusion that it was difficult to tell which was the original reading in the autograph, but that if I had to choose one, I would probably choose to omit the “amen” (because that’s what the editors did).

Textual criticism is crucial, because it can help us decide if the translators did an accurate job with the text. Now, there are many, many different translations, and some people have been known to present the view that because there are so many, it is impossible to know what the Bible truly says. That view is false!

Part 4: English Translations

Works Cited

- The Journey from Texts to Translations: The Origin and Development of the Bible by Dr. Paul D. Wegner

- Lecture at Big Sky Bible Institute by Dr. Paul D. Wegner

We have had a number of presentations in our Sunday school classes over the years discussing the progression of our bible. I always come away a little confused and uncertain. Your descriptions are clear and (especially) concise. Very good presentation! Thank you.

Thanks for the compliment Clint, I'm glad I could be of use by presenting it for you in an understandable manner!